Agencies should set up a process to proactively disclose information that is of interest to the public on an ongoing basis. To help prioritize, agencies should look at requests made through the Freedom of Information Act, via other request-based systems (i.e., specialized forms for a particular dataset or document), and information regularly disclosed by public affairs and congressional relations offices.

Categories of information to consider for proactive release include: commercial (business-related), current events (relevant to journalists), ethics (relevant to government watchdogs, such as lobbying, ethics waivers, etc.), agency operations, and datasets (paper versions are disclosed to the public but the underlying dataset must be FOIA’d).

On a regular basis, each agency should review its efforts to evaluate the effect of proactive disclosure and whether additional documents/datasets should be proactively disclosed.

A Few Ideas on Getting Started

1. — Review how the agency already discloses information to the public.

Agency information is made available to the public in many ways. Some examples include:

- As responses to FOIA requests

- As responses to specialized request forms

- Responses to media inquiries (by email, telephonically, and press advisories and releases)

- As letters or reports to Congress or OMB

- Information the agency is trying to place with media

- Information disclosed in reports (already online) that are not in machine-readable formats

There may be others ways as well. Get a sense of how the public is accessing information.

2. — Get an understanding of how each of these information request processes work and obtain a representative sample of the kinds of requests being answered.

FOIA. Obtain the FOIA logs and randomly choose a significant number of requests (say 500 or 1000). Categorize each request based on the likely purpose for which it will be used: commercial, current events, ethics, agency operations, and datasets. Within each category, figure out whether the requests overlap a common dataset or series of documents.

Responses to specialized request forms. Create a list of the specialized information request forms that an agency uses to receive requests from the public. Determine the volume of requests received, on average, each year. For each form, figure out whether the information is pulled from a particular dataset or set of documents.

Responses to media inquiries. Reach out to press office staff to see whether they keep a media log, which tracks who has called and what they’ve called about. If it is exists, review a representative sample (pick a few random days) to see whether there is any commonality to the requests. Identify and list the most frequent requests. If not, look at releases and advisories pushed out by fax or email.

Reports to Congress or OMB. Make a list of all reports to Congress or OMB. Are they already available online, but not in one central place? Are multiple years grouped together? Are they available through FOIA or published through some other means?

Information to be placed with the media. Speak with press offices to get a sense of the kind of information commonly pushed to the public. Is it available online in one central place? How is the information presented?

Information disclosed but not in machine-friendly formats. Create a list of reports available on the website. Identify whether they are only available as PDF, or are they available in other formats as well, such as csv or doc?

3. — Prioritize

Looking at the information identified above, are there kinds of information that is requested again and again? If so, is it possible to disclose the underlying dataset or series of documents that underpin these common requests? Decide based upon the number of requests and the likelihood of use by the public.

Some clues to look for:

FOIA. Is information drawn from a certain source requested again and again? If so, is it possible to make the source information available to the public? If not, is it possible to create an expedited way of requesting that information? Or to pre-process that information as if it were already the subject of a FOIA request?

Responses to specialized forms. While being sure to include items from each category of information to consider for proactive disclosure, look at the most utilized special forms and determine whether it is possible to release the underlying information all at once.

Responses to media inquiries. Are there kinds of information requested again and again from press staff? Or types of requests that can be anticipated in the news cycle? If so, work with press staff to get ahead of the curve and disclose the information that is frequently requested.

Reports to Congress or OMB. If these reports routinely become available, publish them all online in a central place on the agency website as soon as they are issued. If there are concerns about redactions under FOIA, process through FOIA immediately prior to receiving a request, so they can be released at the same time or as close as possible to when the report is issued.

Information trying to be placed with the media. Publish the information as soon as possible.

Information disclosed but not in machine-readable formats. Work with offices and technology staff to make sure information published as a PDF is also published in other (open) formats as well, such as csv and doc.

4. — Two more things

(i) Talk to external and internal stakeholders. They know where the pain points are and can advise as to what would be most useful.

(ii) Look to see if an entity is broadly republishing the information the agency has provided. For example, some non-profit organizations will request an entire dataset and make it available all at once. In turn, many thousands of people will use that information. Instead of making the organization request that data, publish it online so it is available at once to everyone.

Examples of categories of information:

- Business: Hedge funds using FOIA requests to obtain nonpublic information from federal agencies

- Current events: (anything relevant to journalists) E.g., licenses for crude exports to Europe.

- Ethics: Personal Financial Disclosure Forms from the Office of Government Ethics (requestable one at a time). See also OIRA lobbying information (available as webpages but not dataset).

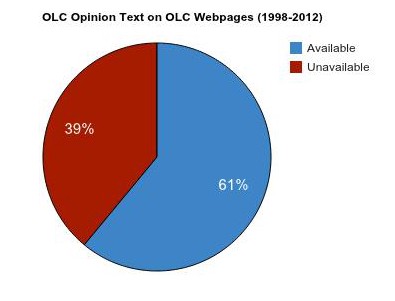

- Agency Operations: Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel Opinions. Some are disclosed on multiple webpages, but not all.

- Datasets: IRS 990s (c(4) tax exempt organizations).

{ Liked this? You may also like A FOIA No-Brainer and A Checklist for Drafters of Transparency Legislation }

— Written by Daniel Schuman