This article was written by Melanie Buck and published by the Sunlight Foundation on December 1, 2010.

Because of a quirk in the law, Adela Bailor was ineligible for compensation for the brutal attack she suffered at the hands of a felon in federal custody. A court concluded that it had no power to hold the government responsible for her attack, even while noting her case “raise[d] serious questions about the moral responsibility of the government to protect its citizens.” In its opinion, the court suggested that she had one last resort: Congress.

Congress has the power to enact “private laws,” a type of legislation narrowly targeted to provide benefits to specifically identified individuals (including corporate bodies) when “no other remedy is available.” Claims of ill treatment and unfair circumstances have prompted many of the 107 proposed private laws currently pending in Congress.

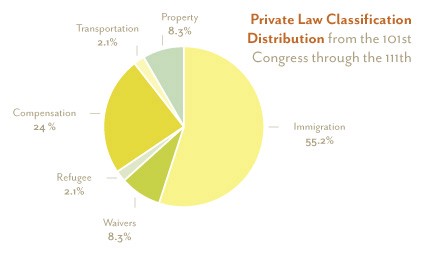

In Ms. Bailor’s case, Rep. Julia Carson introduced legislationin 1997 to give her compensation. Private laws have been used to protect private property, grant waivers for certain federal or legal requirements, provide personal compensation for transgressions by the government, and address refugee or transportation concerns. The majority of bills concern immigration cases. In theory, each private bill represents a petitioner who has exhausted all other options for redress.

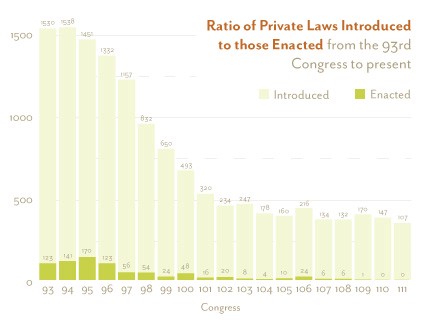

Although once very common, private laws are now rarely enacted into law. House of Representatives Historian Anthony Wallis suggests that their decline stems from the increased ability of administrative bodies to solve these issues. Wallis also says that private provisions are sometimes included in public legislation, thus reducing the need for private laws. That seems rather rare; our review of nearly 2/3s of the 1535 private bills introduced from the 101st to 111th Congress found only 23 instances where private measures were included in public bills. Congress may be phasing out private legislation because of an increasing workload, a concerns about conflicts of interest, and a lack of awareness of how to use this type of legislation.

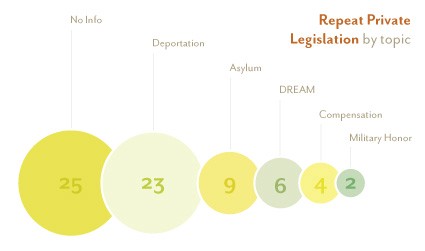

Despite this decreasing frequency of enactment, Members still introduce a significant number of private laws each Congress. Many bills are reintroduced over many Congresses, although few are ultimately acted upon. For example, the legislation regarding Ms. Bailor was introduced in every Congress from the 105th through the 110th. A private bill for the relief of Kadiatou Diallo — the mother of Amadou Diallo — and her family has been introduced in each Congress since the 107th. A private bill for Ibrahim Parlak, a Kurdish immigrant serving jail time in America, has been introduced in each Congress since the 109th. Of the 107 private bills introduced in the 111th Congress, 63 were introduced in previous Congresses.

For the 111th Congress, we examined every private law that was introduced as of October 2010 to see whether we could categorize their subject matter by Googling for the name of the person who is the subject of the bill. Of the repeat private bills that we could classify, almost all concern citizenship issues. 23 pertained to deportation issues involving illegal immigrants, 9 regarded political asylum cases, and the 6 “DREAM Act” cases involved teenagers who had been living in the United States for years without knowing that they were living in the country illegally. The remaining 6 bills compensated individuals wronged by the United States or bestowed military honors.

Historically, private laws could stay deportation so long as they were pending in Congress, but it is unclear whether reforms implemented between 1947 and 1971 have ended this practice.

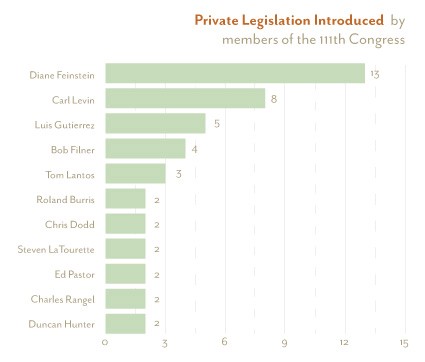

Most private laws are introduced by a small number of Senators and Representatives. Senator Feinstein has the biggest share, with 13 of the 63 repeat bills currently pending.

For Ms. Bailor, the legislative journey appears to have ended when the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Carson, died in 2007.

Sooner or later, all the private bills introduced this term will likely share the same fate.