Drafting legislation may be more art than science, but even the most avan garde artist considers the size of the canvas and the artwork’s composition just as drafters must think through the purposes of the legislation and how circumstances may change over time. What does it take to create robust, effective transparency legislation? Here are some guidelines. At the highest level of abstraction, I suggest drafters:

- Understand the context

- Use flexible implementation authority

- Create external checks on implementation

- Make information public by default

- Build in feedback loops

- Keep close watch on cost

- Watch out for tricky legislative language

- Figure out where to embed a program

1. Understand the context

When inspiration hits, it is useful to explore whether others have tried to solve a similar problem. Looking at other legislation that has been introduced (whether in the current legislative session or earlier ones), searching for testimony before committee and reports that discuss the problem being solved, and identifying reports by outside experts will highlight pitfalls and potential approaches to address an issue.

When inspiration hits, it is useful to explore whether others have tried to solve a similar problem. Looking at other legislation that has been introduced (whether in the current legislative session or earlier ones), searching for testimony before committee and reports that discuss the problem being solved, and identifying reports by outside experts will highlight pitfalls and potential approaches to address an issue.

With transparency legislation in particular, having a sense of what has worked, whether it is considered a success, and how much it costs is an indispensable first step. As you do this, make sure you have a clear sense of what you are trying to accomplish. These goals should be reduced to writing and either be included in the legislation or an accompanying report. This will guide implementation and help ensure that you have created what you intended. As an additional benefit, it also may help with court interpretation should aspects of the program be challenged.

2. Use flexible implementation authority

Within broad constraints, agencies should be given the authority to adapt to the times. For example, a requirement to post a job notice in the classified section of a newspaper makes little sense nowadays as most job seekers look on the Internet. Consequently, requirements regarding how an agency must notify potential job-seekers of an opportunity could be couched in language that requires an ad be placed where it is seen by thousands of people, without indicating the nature of the publication in which it must be published.

Within broad constraints, agencies should be given the authority to adapt to the times. For example, a requirement to post a job notice in the classified section of a newspaper makes little sense nowadays as most job seekers look on the Internet. Consequently, requirements regarding how an agency must notify potential job-seekers of an opportunity could be couched in language that requires an ad be placed where it is seen by thousands of people, without indicating the nature of the publication in which it must be published.

Legislation could include examples of the kinds of places that would satisfy publication requirement, but some discretion should be left up to the administrator. Similarly, the requirement to publish data online should not necessarily specify a particular format in which it must be published. Instead, the legislation should specify characteristics necessary to satisfy a publication requirement.

For example, it could say that data must be published in a structured format that is open, license-free, and capable of being reused. I will talk about data formats more in another blog post, although these principles are a good place to start.

3. Create external checks on implementation

While many agencies operate with the best of intentions, some will fall short by accident or otherwise. It is important to have in place a mechanism for the public (and professional watchdogs) to vindicate the right to full implementation. For example, the only reason the federal FOIA is successful is because it includes a private right of action.

While many agencies operate with the best of intentions, some will fall short by accident or otherwise. It is important to have in place a mechanism for the public (and professional watchdogs) to vindicate the right to full implementation. For example, the only reason the federal FOIA is successful is because it includes a private right of action.

The ability of a requester to go to court is the mechanism that helps encourage/force agencies to adhere to the law, even though this right is exercised only in a small minority of instances. Similar mechanisms exist in other contexts. On the federal level, the IRS, for example, pays money to people who blow the whistle on tax cheats, as does the Department of State for those who help with the apprehension of terrorists. A lawsuit brought under the False Claims Act, often referred to as a qui tam prosecution, allows people who are not affiliated with the federal government to bring a lawsuit against contractors who have defrauded the government.

All these tools empower a neutral third-party outside the agency (and the executive branch) to decide the merits of a claim. Overseas, ombudsmen have become commonplace as an inexpensive way to have a public advocate, paid by the government, address questions of oversight or maladministration.

On a related note, particularly in circumstances where other oversight mechanisms are not robust, we see the crucial role of whistleblowers. Federal whistleblowing law is a hodgepodge of law that often inadequately addressesgovernment misfeasance, malfeasance, and bad practices. Even whistleblowers whose activities are protected by law often suffer significant un-remediated retaliation.

When creating any new program or service, especially those related to reporting on the activities of government, it is essential to think through external mechanisms by which the public may vindicate its rights and the internal mechanisms by which whistleblowers are rewarded and protected when they identify significant problems.

4. Make information public by default

Through the normal course of business agencies create tremendous amounts of information. As a matter of practice, unless there is a very good reason not to that outweighs the public’s interest in disclosure, agencies should publish information on their activities. This can serve good government interests, but also may empower economic development, trust in government, the development of private-public partnerships or private innovation, and other advantages.

Through the normal course of business agencies create tremendous amounts of information. As a matter of practice, unless there is a very good reason not to that outweighs the public’s interest in disclosure, agencies should publish information on their activities. This can serve good government interests, but also may empower economic development, trust in government, the development of private-public partnerships or private innovation, and other advantages.

Elsewhere I have identified a way for agencies to identify and proactively meet requests for information dissemination. It can be summarized as requiring an agency to survey the different means by which information requests come into an agency, consider whether there are commonalities to those requests that can be addressed by discrete sets of information, and then publishing those documents or datasets.

Technology is making proactive disclosure much easier and governments should take full advantage of it. Where should agencies publish this information? On their websites and any places where information is aggregated. On the federal level, reports should be given to the Government Printing Office and raw data should be published on data.gov.

5. Build in feedback loops

Just as it is important to understand how other legislation has fared, equally important is understanding how effective legislation is once enacted. The most successful legislative measures are self-correcting and capable of adapting with the times. Here are some feedback mechanisms that allow this to happen.

Just as it is important to understand how other legislation has fared, equally important is understanding how effective legislation is once enacted. The most successful legislative measures are self-correcting and capable of adapting with the times. Here are some feedback mechanisms that allow this to happen.

Administrative review. At regular intervals, program administrators should evaluate the effectiveness of the programs they administer in attaining their stated goals. These reviews should be accompanied when appropriate by recommendations to adapt the program to changing times consonant with the goals you’ve spelled out in the initial bill.

Public feedback. The public often is an end-user and a source of expertise on a topic. Mechanisms should be put in place for the public to communicate directly to administrators and to the congressional overseers. Just as important, the public must be able to receive a response to their concerns from the administrators and congressional overseers.

This can be accomplished through a designated “public liaison,” a GitHub account, regularly public meetings, and so on. In addition, reports on the effectiveness of programs and proposals to change implementation should routinely be made available to the public in ways that casual users would expect.

Expert feedback. Groups of experts should be invited to regularly provide input into the effectiveness and implementation of programs. At the federal level, this commonly is accomplished through the use of federal advisory committees — a standing group of citizens who regularly interface with program administrators and make recommendations on how program should evolve.

While there are some problems with current federal law that govern how federal advisory committees operate, there are good models to ensure that they are sufficiently transparent and balanced so as to make in a complement to broader public engagement and not merely an avenue for influence by special interests.

Internal auditors. Government auditors may provide crucial insight into how well the program is being administered and whether it is still serving its intended purpose. On the federal level, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the agency inspectors general often play this role. Periodic reviews by GAO and agency IGs (and their equivalents on the state and local levels), including regular reports to the agency, the legislature, and the public, are essential as a good housekeeping matter and will help identify problems as they crop up.

Empowering external review.Requiring an agency or internal oversight body to make reports available to the public and to the legislature is not enough. Legislation should address both the format of the reporting and who must sign off on it before it is transmitted.

Empowering external review.Requiring an agency or internal oversight body to make reports available to the public and to the legislature is not enough. Legislation should address both the format of the reporting and who must sign off on it before it is transmitted.

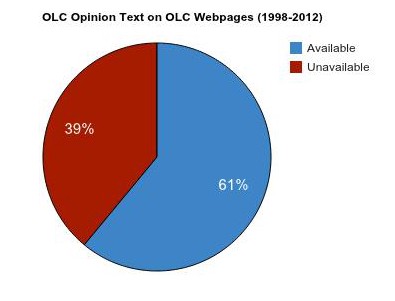

The report’s format is very important. By way of example, for years federal agencies were required to report on their administration of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), but these reports were provided as PDFs even though they containing tables of numbers. Consequently, anyone wishing to evaluate the data would first have to transform the information into a digital format, an arduous and time-consuming task.

Requiring the reporting of FOIA data as an electronic spreadsheet has empowered much greater oversight of agency effectiveness and made the analysis available in near real-time. The use of dashboards creates a powerful incentive for across-the-board compliance with program goals. Reports — especially those containing policy recommendations — should be allowed (and often times required) to go directly from the entity making the recommendations to the legislature and the public.

We have seen that when agency reports must go up the food chain, especially when they are politically sensitive, the report can be held indefinitely or altered prior to publication. An even more insidious form arises when senior administration officials threaten an agency’s budget if a report is not altered. While it is not inappropriate for senior agency officials or others to be allowed to comment on a report, and in some instances to have a heads-up prior to release, all too often the substance is sacrificed for political reasons. Direct reporting authority on policy recommendations is a must to make sure the feedback loop functions properly.

Generally speaking, reports — whether generated by an agency, an IG, external auditors, or others — should be kept in a central location in addition to publishing on the agency and committee of jurisdiction’s website. At the federal level, the Government Printing Office maintains a website containing thousands of documents. All reports should be submitted to GPO (or a similar entity playing a repository role) for safekeeping and online access in addition to any other means of dissemination. This ensures reports are available to the public even after an agency “refreshes” its website, committee staff turnover, and so on.

6. Keep close watch on cost

Nothing will sink a bill faster than a high price tag. For transparency bills, there are useful ways of addressing a high price tag. To the extent information publication mechanisms exist, such as GPO’s FDSYS and data.gov, they should be used instead of building new websites.

Nothing will sink a bill faster than a high price tag. For transparency bills, there are useful ways of addressing a high price tag. To the extent information publication mechanisms exist, such as GPO’s FDSYS and data.gov, they should be used instead of building new websites.

Publication of bulk data by the government will often spur non-profits and others to build more clever websites than the government would have built itself, and at a lower cost. Similarly, if there are commonly-accepted methods of redacting sensitive information, agencies should make use of those systems, and make sure that information once processed is released to the public, and not processed every time a request is received.

In addition, legislation should require agencies to gather and publish the information they use, and to use the information they publish. Requiring agencies to “eat their own dogfood” will help address data quality issues and make sure the public has access to the real deal.

It is important to decide strategically how the public and experts will weigh in programs. While advisory committees, IG reports, and the like are very valuable, an all-of-the-above strategy can be expensive. If pressed for money, figure out where you’re likely to get the most bank for the buck.

Also, consider whether you want your transparency program to be independent or embedded in an existing agency. Creating a new thing can be costly, so determine whether it is necessary to protect implementation from undue interference. There is no magic bullet to identifying hidden implementation issues that can balloon costs once a program is underway. The best advice is to talk to staff who must implement the legislation, keeping in mind they may have an ax to grind or be unwilling to talk.

Former staff can be helpful in circumventing some political problems with obtaining honest advice. Sometimes outside non-profits will have built models that accomplish what the transparency legislation is trying to achieve, and they can be a useful source of expertise identifying pitfalls.

7. Watch out for tricky legislative language

Drafting legislative language, especially when a bill is meant to be generally applicable to the government, can be quite tricky. Here are couple common pitfalls.

Drafting legislative language, especially when a bill is meant to be generally applicable to the government, can be quite tricky. Here are couple common pitfalls.

Definition of Agency. Although one might think that there would be a single definition for agency there is not. For example, on the federal level, the term “agency” is defined in multiple places in the US code and you should pick the kind of agency that best reflects your goals.

Do you want to cover the entire executive branch? Do you wish only to cover the agencies inside the executive branch that are under the control the president (and thus preserve the independence of the so-called independent executive branch agencies)? Do you want to include legislative and judicial agencies as well?

In all the circumstances, have you thought through the separation of powers issues that arise from the scope of your definition of agency?

Definition of Record. When referring to how the government stories information, the term of art is often a “record,” at least at the federal level. But record is defined in various ways throughout the US Code. It is important to cite to the definition that you want and know what it does and does not cover.

Level of detail. This is a tricky matter. Legislative staff — particularly senior staff — strongly prefer to avoid too much detail in legislation. Agencies in some circumstances really dislike detailed instructions. However, a significant level of detail is necessary to ensure agency staffers comply with congressional intent (and give them protection so they can say they are following the law). While it is helpful to include finding in the legislation or committee report, this is an issue that often must be negotiated.

Budget Score. At the federal level, all legislation must be scored by the Congressional Budget Office. Too high a cost estimate can sink even the most promising bill, even if the bill will save more money than it costs, in part because the Congressional Budget Office engages in static scoring. There are a handful of tricks that often are employed to keep the cost projections down. For example, the date of full implementation of a program often is a decade after the legislation is enacted. Or another program is found to be eliminated as an offset.

Inclusive/ exclusive lists. Often times, legislative language includes a list of what an agency should do. For example, it may say: “For the purposes outlined above, the agency report should include, but not be limited to, X, Y, and Z.” However, this is often read by agencies as saying the must only do X, Y, and Z. A slightly better form is “for the purposes outline above, the agency report should include, X, Y, Z, and all other items that further the purpose….” Be aware that lists can often be interpreted as excluding behavior, not just requiring it. Smart legislation will also require disclosure of interpretations of language by agencies.

FOIA. Legislators often look for a formula to make sure sensitive information is withheld. Often times, at the federal level, the easiest way to do this is to include the FOIA disclosure exemptions (see 5 USC 552(b)) to say what can be withheld.

FOIA. Legislators often look for a formula to make sure sensitive information is withheld. Often times, at the federal level, the easiest way to do this is to include the FOIA disclosure exemptions (see 5 USC 552(b)) to say what can be withheld.

However, be sure to include a balancing test whenever invoking that section of law. Something like, “Unless required to be withheld under law, records should be made available to the public unless the public’s interest in disclosure is significantly outweighed by the agency’s interest in withholding the records under the exemptions outlined in 5 USC 552(b).” In many instances, you can narrow further beyond the FOIA exemptions, which often are too protective.

Principles of statutory interpretation. Courts use many rules to interpret legislation to determine legislative intent. For all practical purposes, for every rule that says X there’s another rule of interpretation that says the opposite. Even so, this Congressional Research Service report may be helpful in determining how a court would interpret particular language.

Borrow language. Policymakers are most comfortable with language that has been used before. Scour current law or already drafted bills for legislative language. Sometimes members will introduce message legislation that includes a broad range of transparency measures (such as the Transparency in Government Act). While the entire bill will never pass as is, there’s nothing wrong with pulling apart the bill and piggybacking on existing language. That’s why it exists. Similarly, it is best to keep language as simple as possible unless your goal is to confuse review and evade oversight.

Get a lawyer. Spotting potentially ambiguous language is something lawyers do best. Get a good one (or multiple attorneys) to try to identify and address any legislative loopholes.

Committee jurisdiction. Usually, the fewer committees that have jurisdiction over a bill the fewer complications. The right language can keep a bill from being referred to an unfriendly committee or referral to multiple committees. The language you use will determine its path.

Naming the bill. While it’s not strictly legislative language, at least one academic study indicated the name of a bill does affect its likelihood of passage. It’s stupid, but the name is all that many people look at. So pick a snappy name or acronym and has a positive connotation.

8. Figure out where to embed the program

For programs that affect multiple agencies, consider where to house the program. Each of the potential locations has attendant risks and benefits. For example, at the federal level, the Office of Management and Budget has great authority executive branch (non-independent) agencies and expertise with rulemaking. However, it also is close to the White House and has a dual role of protecting the president’s agenda.

For programs that affect multiple agencies, consider where to house the program. Each of the potential locations has attendant risks and benefits. For example, at the federal level, the Office of Management and Budget has great authority executive branch (non-independent) agencies and expertise with rulemaking. However, it also is close to the White House and has a dual role of protecting the president’s agenda.

Sometimes these wires get crossed. The General Services Administration, as an independent agency, is viewed as more impartial by other agencies. However, it generally does not enjoy the extensive rulemaking authority used by OMB and has a mixed reputation, even though it has been successful in a number of areas.

The Treasury Department, while an executive branch agency, has particular expertise in fiscal matters and in some instances may be a better fit than OMB. Legislative branch agencies are more likely to be independent of the White House than even independent executive branch agencies. The Congressional Budget Office is a more trusted source for independent evaluation of the president’s budget than OMB; Congressional Research Service reports are more dispassionate than opinions from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel; the Government Accountability Office provides more independent oversight than OMB, etc.

Some programs can be embedded in multiple agencies. This can be problematic when one agency must consult with another. Having a clear decision-making authority, with only the need to consult other agencies, often is preferable to requiring the consent of another agency to proceed.

Concluding Thoughts

A lot goes into drafting successful transparency legislation and this blogpost only scratched the surface. Not discussed are all the political considerations, how to find the right sponsors and identify allies, how to prioritize ideas, whether the bill is intended as model legislation or addressing a particular target, naming and marketing the bill to the legislature and the press, navigating committee jurisdiction, and so forth. You could write a book about those topics.

For my part, future blogposts will identify language from current federal legislation that is worth borrowing and go into detail about language to use when talking about data. I’d love to hear your feedback.

{ Liked this? You may also like A FOIA No-Brainer and How Agencies Can Improve Proactice Disclosure }

— Written by Daniel Schuman

When inspiration hits, it is useful to explore whether others have tried to solve a similar problem. Looking at other legislation that has been introduced (whether in the current legislative session or earlier ones), searching for testimony before committee and reports that discuss the problem being solved, and identifying reports by outside experts will highlight pitfalls and potential approaches to address an issue.

When inspiration hits, it is useful to explore whether others have tried to solve a similar problem. Looking at other legislation that has been introduced (whether in the current legislative session or earlier ones), searching for testimony before committee and reports that discuss the problem being solved, and identifying reports by outside experts will highlight pitfalls and potential approaches to address an issue. Within broad constraints, agencies should be given the authority to adapt to the times. For example, a requirement to post a job notice in the classified section of a newspaper makes little sense nowadays as most job seekers look on the Internet. Consequently, requirements regarding how an agency must notify potential job-seekers of an opportunity could be couched in language that requires an ad be placed where it is seen by thousands of people, without indicating the nature of the publication in which it must be published.

Within broad constraints, agencies should be given the authority to adapt to the times. For example, a requirement to post a job notice in the classified section of a newspaper makes little sense nowadays as most job seekers look on the Internet. Consequently, requirements regarding how an agency must notify potential job-seekers of an opportunity could be couched in language that requires an ad be placed where it is seen by thousands of people, without indicating the nature of the publication in which it must be published. While many agencies operate with the best of intentions, some will fall short by accident or otherwise. It is important to have in place a mechanism for the public (and professional watchdogs) to vindicate the right to full implementation. For example, the only reason the federal FOIA is successful is because it includes a private right of action.

While many agencies operate with the best of intentions, some will fall short by accident or otherwise. It is important to have in place a mechanism for the public (and professional watchdogs) to vindicate the right to full implementation. For example, the only reason the federal FOIA is successful is because it includes a private right of action. Through the normal course of business agencies create tremendous amounts of information. As a matter of practice, unless there is a very good reason not to that outweighs the public’s interest in disclosure, agencies should publish information on their activities. This can serve good government interests, but also may empower economic development, trust in government, the development of private-public partnerships or private innovation, and other advantages.

Through the normal course of business agencies create tremendous amounts of information. As a matter of practice, unless there is a very good reason not to that outweighs the public’s interest in disclosure, agencies should publish information on their activities. This can serve good government interests, but also may empower economic development, trust in government, the development of private-public partnerships or private innovation, and other advantages. Just as it is important to understand how other legislation has fared, equally important is understanding how effective legislation is once enacted. The most successful legislative measures are self-correcting and capable of adapting with the times. Here are some feedback mechanisms that allow this to happen.

Just as it is important to understand how other legislation has fared, equally important is understanding how effective legislation is once enacted. The most successful legislative measures are self-correcting and capable of adapting with the times. Here are some feedback mechanisms that allow this to happen. Empowering external review.Requiring an agency or internal oversight body to make reports available to the public and to the legislature is not enough. Legislation should address both the format of the reporting and who must sign off on it before it is transmitted.

Empowering external review.Requiring an agency or internal oversight body to make reports available to the public and to the legislature is not enough. Legislation should address both the format of the reporting and who must sign off on it before it is transmitted. Nothing will sink a bill faster than a high price tag. For transparency bills, there are useful ways of addressing a high price tag. To the extent information publication mechanisms exist, such as GPO’s FDSYS and data.gov, they should be used instead of building new websites.

Nothing will sink a bill faster than a high price tag. For transparency bills, there are useful ways of addressing a high price tag. To the extent information publication mechanisms exist, such as GPO’s FDSYS and data.gov, they should be used instead of building new websites. Drafting legislative language, especially when a bill is meant to be generally applicable to the government, can be quite tricky. Here are couple common pitfalls.

Drafting legislative language, especially when a bill is meant to be generally applicable to the government, can be quite tricky. Here are couple common pitfalls. FOIA. Legislators often look for a formula to make sure sensitive information is withheld. Often times, at the federal level, the easiest way to do this is to include the FOIA disclosure exemptions (see 5 USC 552(b)) to say what can be withheld.

FOIA. Legislators often look for a formula to make sure sensitive information is withheld. Often times, at the federal level, the easiest way to do this is to include the FOIA disclosure exemptions (see 5 USC 552(b)) to say what can be withheld. For programs that affect multiple agencies, consider where to house the program. Each of the potential locations has attendant risks and benefits. For example, at the federal level, the Office of Management and Budget has great authority executive branch (non-independent) agencies and expertise with rulemaking. However, it also is close to the White House and has a dual role of protecting the president’s agenda.

For programs that affect multiple agencies, consider where to house the program. Each of the potential locations has attendant risks and benefits. For example, at the federal level, the Office of Management and Budget has great authority executive branch (non-independent) agencies and expertise with rulemaking. However, it also is close to the White House and has a dual role of protecting the president’s agenda.