It isn’t sexy, but you have to commend House Republicans for their focus on congressional process, particularly in the negotiations surrounding the selection of a new Speaker of the House of Representatives. Unlike House Democrats and both parties in the Senate, House Republicans publish their internal rules. And, unlike House Democrats, whose leadership, unfortunately, appears unlikely to consider changes to their rules — there is a serious conversation about “regular order” taking place on the majority side of the aisle.

Rules matter. A lot. As Rep. John Dingell famously said,

I’ll let you write the substance. You let me write the procedure, and I‘ll screw you every time.

I’m a rules nerd. For the last six years, I have published suggestions on how the House and Senate should change their rules. Today I’m going to focus on how a small change to the Republican Conference Rules would effect congressional oversight, national security, and civil liberties. (The “Republican Conference” is the official grouping of congressional Republicans.)

Republican Conference rules govern which Republicans may serve on a particular committee. Personnel choices are policy choices, as who you put on a committee determines what it does. The process for choosing members and leadership is different for standing committees and select committees.

Standing committee members are nominated by a special committee, known as the Steering Committee; select committee members are nominated by the Speaker alone. In both instances, the members of the Republican Conference could decline to approve the nominations, but that is unlikely. Almost every committee is a standing committee, except for the Intelligence Committee and the Benghazi Committee, which are select committees.

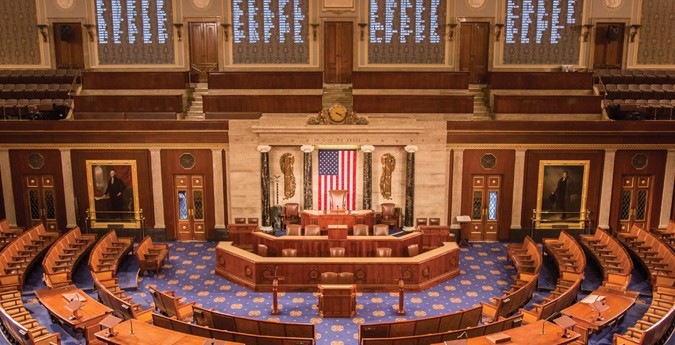

In practice, what this means is the Speaker picks who serves on — and leads — the Intelligence Committee. By comparison, members of the Republican Conference have some influence over the composition of other committees, through the Steering Committee, although even in those circumstances the Speaker has outsized influence.

Consequently, the Intelligence Committee most closely reflects the views of the Speaker when compared to other committees. There is no compelling reason for the Speaker to play this role and many reasons why the Speaker should not. Many committees deal with secrets, including the Armed Services and Appropriations Committees. Select committees usually are temporary, but the House Intelligence Committee has existed since the 1970s. And the House Intelligence Committee is not functioning as it should.

While it would not solve all the problems with intelligence oversight, nomination of members of the House Intelligence Committee should be handled in the same way as members of other committees, to better reflect the diverse perspectives and competencies of the whole House. To do this, House Republican Conference rule 12(a) could be amended to read as follows:

The Republican Steering Committee shall recommend to the Republican Conference the Republican Members of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the standing committees of the House of Representatives, except as otherwise provided in this rule.

The Rules of the House of Representatives place a few limitations on the pool of candidates. (See page 14, subsection x.) But there’s no reason why this cannot be handled by the Steering Committee or through some other process.

The House of Representatives cannot afford to fail in its responsibilities to oversee the intelligence community. Members of the House of Representatives should take responsibility for oversight into their own hands by making sure the House Intelligence Committee reflects their priorities and the will of the House.

— Written by Daniel Schuman