Today armed Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol in an apparent and temporarily successful effort to disrupt the vote to certify the 2020 presidential election results. Members, staff, and journalists were forced to hide throughout the terrifying ordeal and many took to Twitter asking the fundamental questions: Where are the Capitol Police and how could this happen?

The U.S. Capitol Police is the security-force/police-department hybrid tasked with keeping Congress safe and open for business. The little-known department has a budget that exceeds $515 million for FY 2021— constituting almost 10% of Legislative branch funding — and nearly 2,450 employees, around 2,000 of whom are sworn officers. The size of the Capitol Police’s budget can compete with major municipal police forces such as San Antonio’s, which is responsible for a population of 1.5 million, and USCP’s workforce size eclipses that of major city departments like New Orleans and Miami. Notably, their extended jurisdiction covers less than 2 square miles, and there are many other police and security forces in Washington, D.C.

How is the department using those resources to enforce the law and protect the Congress? It is difficult to say because the Capitol Police are infamously opaque. Only in response to significant outside agitation did we obtain any details about their operations. For example, the department started posting weekly arrest summaries in December 2018, following prodding from civil society and congressional overseers. These summaries are among the limited information the department shares publicly — although we have reason to suspect they are not complete, among other shortcomings.

The Capitol Police does have an Inspector General. However, unlike the vast majority of IGs, the USCP IG does not make their reports publicly available. In addition, the Capitol Police does publish basic information about complaints against them, but most notable for its lack of detail. Additionally, it is possible to request information from the Capitol Police concerning arrests, but our experience is that they often do not comply with the requests for information. Finally, while there is a public affairs office, our repeated experience is that they are in the business of not responding to inquiries and take a generally dim attitude towards public requests for information.

To their immense credit, the Committee on House Administration dove deeply into the Capitol Police’s operations during a 2019 hearing, uncovering issues like allegations of discrimination. The committee has demonstrated a commitment to improving the transparency and efficacy of the department. In addition, Ranking Member Rodney Davis (R-IL) introduced the Capitol Police Advancement Act in July which contained several notable improvements to their operations.

There have been recent successful legislative efforts to impose some measure of transparency and accountability of the Capitol Police. For example, the House’s Legislative Branch Appropriation committee included a number of significant reforms in the Appropriations/COVID Omnibus that was belatedly signed into law last week. Among the provisions in the legislation are:

- Creation of a FOIA-like process and procedure for the Capitol Police (who are not currently required to disclose information);

- Review of Inspector General reports to identify which ones should be publicly available;

- Publication of arrest information in a structured data-format with significant detail;

- Report on arrests made outside the primary jurisdiction;

- Various measures that address racism and diversity among the policy force and how it engages with the public.

While these changes are most welcome, they were not implemented in time to provide insight into USCP operations. The Capitol Police are immediately supervised by the Oversight Board, which is composed of the House and Senate Sergeants at Arms and the Architect of the Capitol. Oddly, the Capitol Police Chief is an ex-officio member of the Board. This has the effect of shielding the Capitol Police from public accountability as the Board activities are not publicly available. Ultimately, both chambers of Congress are responsible for the USCP.

We took a deep dive into Capitol Police activities, based on publicly-reported information, to try to understand how they spend their time. If the past two years of arrest data reflect department priorities, we can see where they place a significant part of their emphasis:

- Half of the incidents reported are traffic stops: Of the 745 incidents that occured between December 19, 2018 and December 19, 2020 51.7% (385) included charges for traffic-related infractions. Furthermore, 14.2% (106) of incidents were drug related, with drug related defined as reports including the terms “marijuana,” “powder,” “substance,” “pipe,” “joint,” “paraphernalia,” or “leafy.”

- The majority of policing activity happens when Congress is done for the day: more than 60% (476) of reported incidents occurred outside business hours, defined as 7:30 am to 6:30 pm Monday through Friday, holidays included.

- Only a third of arrests happen on the immediate Capitol Campus, with just 32.2% (240) of all incidents reported occurring in House and Senate office buildings, the U.S. Capitol, and/or on the streets directly adjacent to these locations. Meanwhile more than 13% of incidents (98) took place within the one block radius surrounding Union Station.

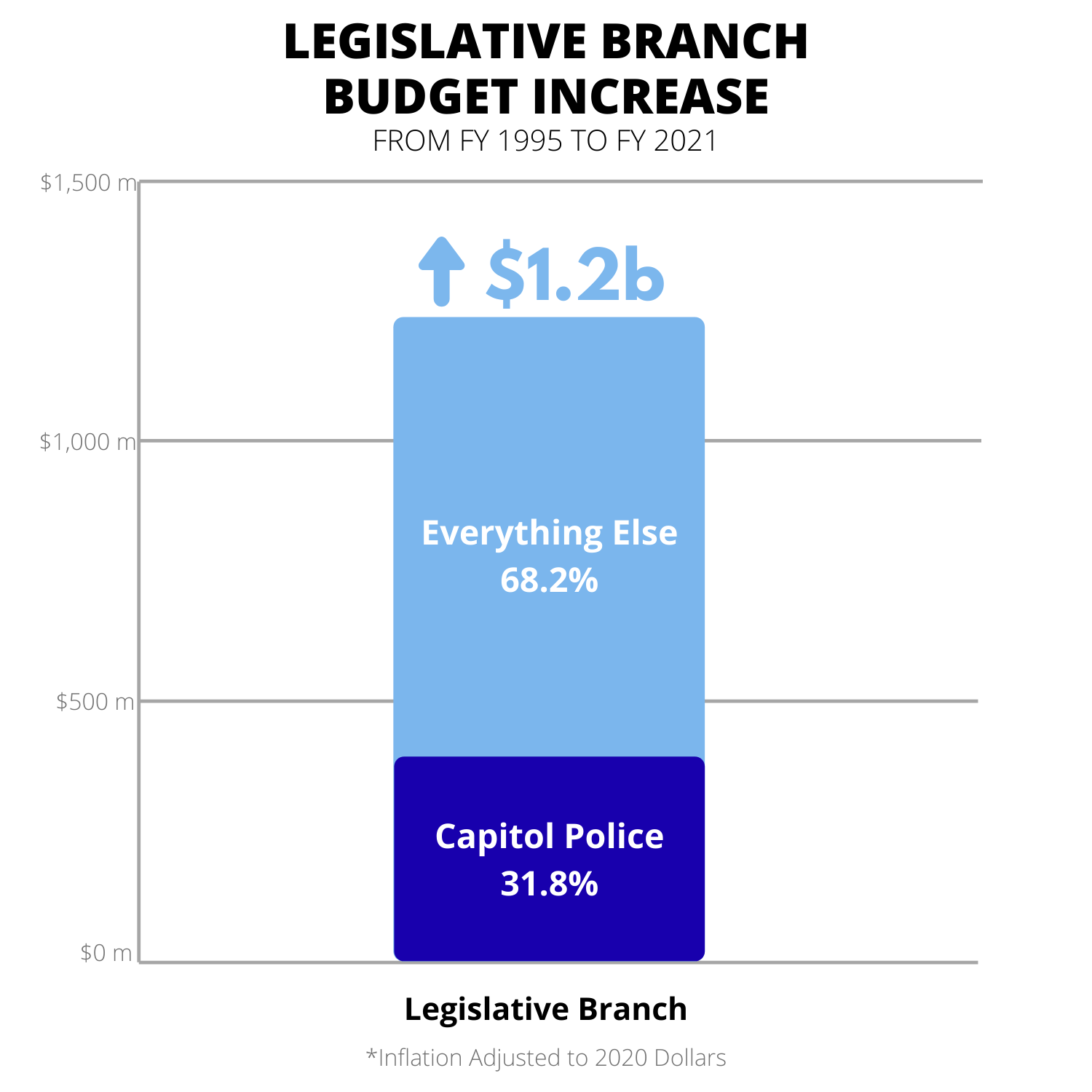

With an abundance of resources, how is it possible the department wasn’t prepared for yesterday’s events? The answer could be, in part, insufficient accountability mechanisms. The department has had money thrown at it for years — its budget is up 322.9% from 1995 (adjusting for inflation), whereas the Legislative Branch Budget has only grown 30.5% in that same time — but those dollars haven’t come with the necessary oversight strings attached. It is apparent that money is not the problem.

We suspect that the Capitol Police has failed to properly invest in its personnel and practices. Furthermore, while they have a significant intelligence-related function, clearly it was insufficient to the moment, even as it was obvious to outside observers that this could happen.

We are distraught by today’s events. We are concerned for the safety of Members of Congress, their staff, capitol employees, the press, visitors, and the Capitol Police themselves. This never should have happened — but as our research suggests that inadequate oversight and accountability over the decades left the Capitol Police gravely incapable of meeting the moment.

— Written by Amelia Strauss and Daniel Schuman

3 thoughts on “A Primer on the Capitol Police: What We Know From Two Years of Research”

Comments are closed.