Yesterday’s appointment of representative Joaquin Castro (D-TX) to the House Intelligence Committee may push the Committee’s membership out of balance — it no longer has a member who also serves on the Judiciary Committee, as required by the Rules of the House of Representatives.

Because of its coordinating role, House Rules require the Committee to include at least one member who also serves on the following committees: Appropriations, Armed Services, Foreign Affairs, and Judiciary. Rep. Castro replaces Illinois representative Luis Gutierrez, who resigned on May 26th and was the only member of the Committee cross-seated on Judiciary. The House of Representatives apparently waived the rules’ requirement when it agreed to his appointment.

Unlike most congressional committees, Intelligence Committee members are chosen by the House Speaker and Minority Leader. The Committee itself is subject to different rules and responsibilities than permanent standing committees. It has responsibility for oversight of the Intelligence Community.

A staff study by the House Intelligence Committee in the mid 1990s explained that the purpose of cross-seating is to “broaden the oversight base [by including] Members from other committees that have an interest in intelligence or intelligence related issues.” The 9/11 Commission embraced the notion of cross-seating in its report, explaining that “in this way the other major congressional interests can be brought together in the new committee’s work.” The underlying notion is that committees with overlapping jurisdiction and different priorities should have a voice on the Intelligence Committee, and in turn the work of that Committee can feed back to the work of others.

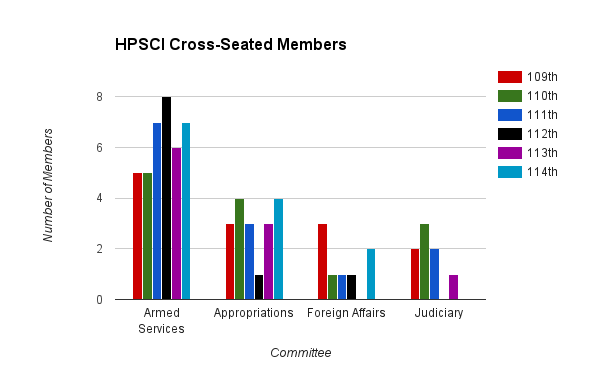

With the help of GovTrack.us, we reviewed cross-seating in the House Intelligence Committee over the last dozen years. Unfortunately, there are significant limitations in the data, so we could not make a definitive analysis.* The findings suggest there are two other instances since 2005 where the Committee lacked its full complement of cross-seated members: in the 113th Congress there was not a representative from the Foreign Affairs Committee; and in the 112th Congress there was not a representative from the Judiciary Committee.

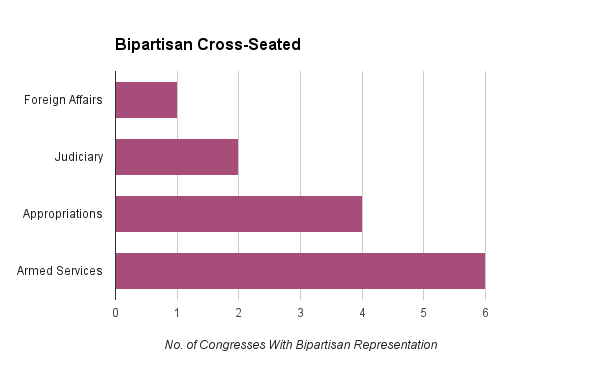

Generally speaking, the four cross-seated committees have had at least one member on the Intelligence Committee. Often times, they had one from each party.

• • •

While incomplete, the data suggests several conclusions.

First, historically speaking, the Armed Services committee has a large contingent on the 22 member committee. Similarly, the Judiciary and Foreign Affairs committees are comparatively under-represented, and in some instances have not been represented at all.

Second, the non-representation of the Judiciary Committee this Congress poses potential problems in the future. Depending on the turnover at the end of this Congress, it is likely that the Intelligence Committee will continue to under-represent the perspectives of the Judiciary and Foreign Affairs committees. We may see an Intelligence Committee that has no Judiciary Committee members next Congress.

Third, there are many qualified members of the Judiciary Committee who could have been tapped to serve on the Intelligence Committee, so the selection of Rep. Castro may have been intended in part to address a political consideration arising from inter-party dynamics. If so, it may be worth investigating why the composition of the Judiciary Committee was insufficient to address this problem. In addition, the non-selection may undermine the important role cross-seating is intended to address.

Fourth, as we saw this Congress with the debates over the USA PATRIOT Act renewal, the Judiciary Committee encompasses a broader range of perspectives and takes a comparatively tempered approach to questions of national security and civil liberties. The next Congress will have a significant debate over warrantless surveillance with the expiration of section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act. The Judiciary committee will continue to be underrepresented and Armed Services will have a large presence. As a potential consequence, the House Intelligence Committee may continue to be more hawkish than the House as a whole. Members of Congress more likely to have a skeptical attitude towards the Intelligence Community are less likely to be in a position to exercise oversight, a problem exacerbating by the largely secret work of the Committee.

Finally, the Intelligence Committee does not receive the full benefits of bipartisan representation from a cross-seated committee members. In light of modern partisan politics, there may be value with ensuring the majority and the minority of cross-seated committees have representation on the Intelligence Committee.

• • •

** Here are the points in time where the Intelligence Committee data was gathered.

- 109th Congress: 2006–12–31 09:18:35

- 110th Congress: 2008–05–20 20:30:36

- 111th Congress: 2010–06–12 11:34:16

- 112th Congress: 2012–06–23 15:01:53

- 113th Congress: 2014–04–03 02:45:15

- 114th Congress: July 6, 2016

— Written by Daniel Schuman